Last week, two senior US lawmakers asked the Pentagon to add Chinese battery maker Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited, (CATL) to a list of companies that cannot receive US military contracts, because of its alleged ties to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). The company defended itself, claiming CATL "is not controlled by the Chinese government." But across the private sector in China, the distinction between the state and private firms has become blurred over the past decade. Since Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has methodically pursued a policy of expanded control and oversight of the private sector. Today, the party has a much greater ability to monitor and influence the decision-making of private Chinese firms. Such influence has profound implications for the United States and other Western governments seeking to recalibrate their economic relationship with Beijing.

The government and party use several approaches to secure this control and oversight of the business community. CCP cells have expanded greatly inside company headquarters. Changes in corporate governance as well as party officials placed into the corporate hierarchy have elevated the party’s role in business decisions. Government subsidies and contracts increase the private sector’s dependency on Beijing. And joint ventures and mixed-ownership investments tie private firms to state-owned enterprises. CATL exemplifies all these approaches toward the growing fusion of state and private enterprises.

Although People’s Republic of China government officials dismiss accusations of party control over the private sector, the policy shift has long been recognized by some in China’s business community. Speaking in 2018, Wang Xiaochuan, chief executive of Tencent subsidiary Sogou, spoke about the implications of this policy shift for China’s private entrepreneurs:

We’re entering an era in which we’ll be fused together. It might be that there will be a request to establish a party committee within your company, or that you should let state investors take a stake, you know, as a form of mixed ownership. If you think clearly about this…you can receive massive support. But if it’s your nature to go your own way, to think that your interests differ from what the state is advocating, then you’ll probably find that things are painful, more painful than in the past.

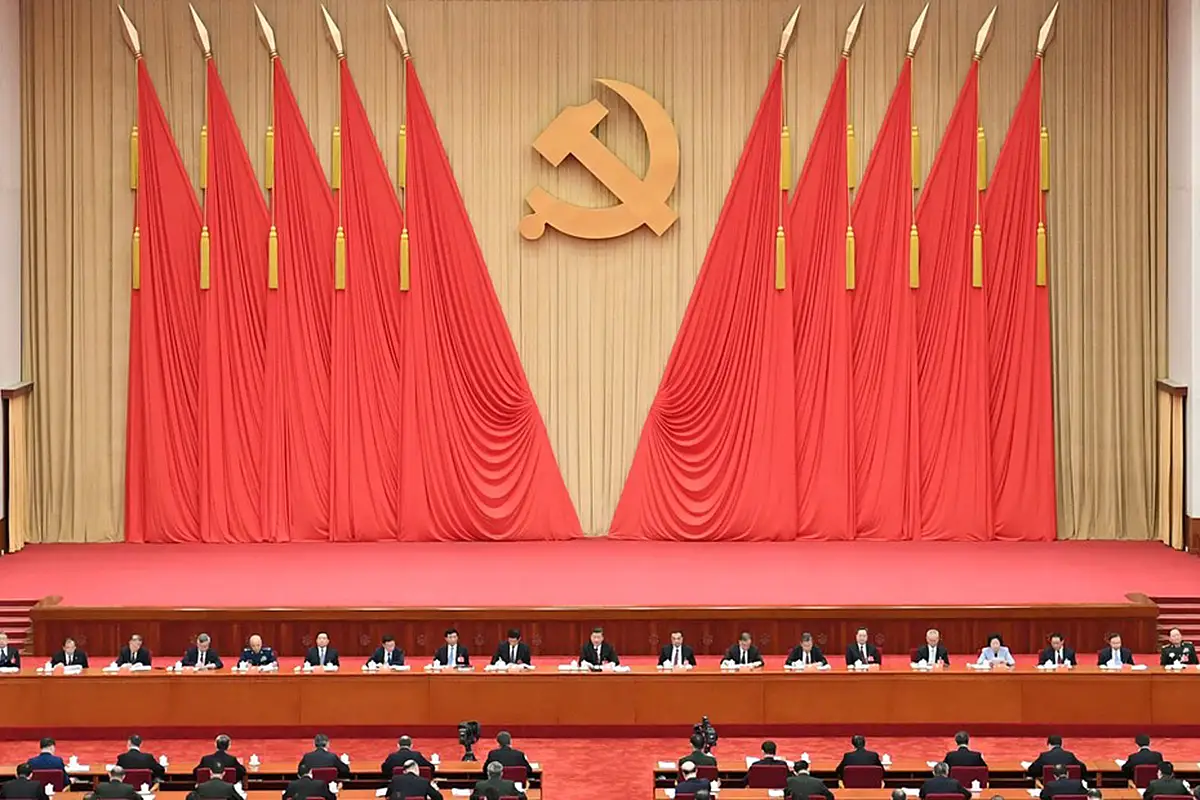

The Party’s Relationship with Business under Xi Jinping

Party influence over the business community requires a more robust presence in that community. Xi Jinping raised this issue explicitly in his first year in power, as he referred to the CCP’s foundation within the private sector as “weak” (工作基础薄弱) and emphasized the need to “carry out the party’s work and enhance the party’s influence.” Subsequently, the CCP intensified its efforts to integrate itself into the private sector and promote party building in private enterprises, enhancing its monitoring capacity. By 2017, nearly three-quarters of private enterprises had an established CCP cell, and by 2021, the party had “achieved complete coverage” (全覆盖) of all 500 of the nation’s largest private firms.

Once the CCP’s presence in the private sector was solidly established, both state mechanisms and the firms themselves began elevating the party's role in corporate governance. Between 2015 and 2018, over 180 private firms amended their articles of association to formalize the corporate governance role of their CCP organizations. In 2018, the China Securities Regulatory Commission implemented a revised “Code of Corporate Governance for Listed Firms,” mandating all listed Chinese firms support party building activities. The party has also proactively dispatched (派到) officials to serve in leadership roles in private firms. For example, in 2019, the Hangzhou municipal government placed officials in 100 key private firms, including Geeley and Alibaba. In 2023, the Shaanxi Provincial CCP Organizational Department dispatched 25 First Party Secretaries to serve in 25 priority enterprises province-wide.

CATL, a major player in the global market for electric vehicle batteries, serves as an excellent example of this evolution of the party’s role in the private sector. The CCP has worked diligently to establish a strong presence within the company. By 2021, CATL’s flagship headquarters had 28 distinct CCP branches. In 2022, CATL’s board amended the company’s articles of association to emphasize the importance of “the construction of party organizations” (党组织的建设) within the firm.

CATL’s Party Committee has actively sought to expand cooperation with external CCP organizations as well, including those in defense research institutes working with the PLA. In April 2021, the company welcomed a delegation from the Beihang University to hear about CATL’s approach to party building and the party’s role in the development of the electric vehicle battery industry. Beihang is one of China’s “Seven Son’s of National Defense” (国防七子), research institutes with direct ties to the PLA and China’s defense industry. The delegation toured CATL’s Party Building Memorial Hall and, together with CATL party members, made a pilgrimage to a local museum commemorating the code breaking and intelligence work of a former director of the Red Army Headquarters Second Bureau.

Blurring Distinctions Between Private and State Firms

In addition to embedding itself within private firms, the CCP has strategically altered the business environment by blurring distinctions between state and private enterprises. From 2000 to 2019, the share of private firms receiving investments from state-owned enterprises or heavily reliant on state capital more than doubled, to 35 percent of all registered capital. Today, firms in which the state has invested directly are responsible for almost half of all private assets in China.

CATL also exemplifies these practical connections between the state and private firms. In the first half of 2023 alone, CATL reportedly received some 2.85 billion renminbi (over $390 million) in government subsidies, making it the top recipient among all A-share listed companies in China. Moreover, CATL has established multiple joint ventures with state-owned enterprises. One of these is with a subsidiary of Guangdong Hongda Holdings, part of a larger state-owned conglomerate that produces advanced military hardware, including the HD-1 supersonic missile.

While direct evidence of Beijing's intervention in the specific decisions of private firms is rare—the system’s design favors indirect influence through incentives and constraints—examples do occasionally surface. In 2023, Xi met with a group of prominent businessmen including CATL founder and chairman Robin Zeng and expressed concern about the risks of CATL’s global expansion:

While it is gratifying that our industries are world leaders, I am concerned that this sudden burst [of growth] may abruptly end. You [Robin Zeng] mentioned upstream [critical] minerals. Countries might 'pinch our necks' right from the source.…We must prevent a situation where we advance confidently but end up being ambushed and completely defeated. In the context of a zero-sum game with others, we must leave ourselves an escape route!

Days after the meeting, the China Security Regulatory Commission issued informal instructions to CATL requesting that it pare back its plans to raise $5 billion in Swiss global depository receipts, which CATL had planned to use to fund its European expansion. CATL delayed the listing indefinitely.

To be sure, private firms in China do retain agency and remain motivated by financial incentives; they are not merely extensions of the state. Although the CCP under Xi Jinping has intensified its efforts to assert control over the private sector, Chinese private firms have been creative in their efforts to navigate central policies, often finding innovative ways to carve out operational autonomy within challenging environments.

From a policy perspective, however, the CCP’s efforts to blur the boundaries between the state and the private sector carry profound implications for how the United States and the West should interact with private Chinese firms. While corporations like TikTok owner ByteDance, drone maker DJI, or maritime infrastructure firm Landbridge Group may be primarily focused on their bottom lines, their ability to reject CCP requests for information, access, or even direct action is likely to be limited only by Beijing ability to enforce its intended policies. This reality underscores the necessity of changes to US approaches toward China’s private sector.